What is EternalBlue?

EternalBlue is both the given name to a series of Microsoft software vulnerabilities and the exploit created by the NSA as a cyberattack tool. Although the EternalBlue exploit — officially named MS17-010 by Microsoft — affects only Windows operating systems, anything that uses the SMBv1 (Server Message Block version 1) file-sharing protocol is technically at risk of being targeted for ransomware and other cyberattacks.

How was EternalBlue developed?

You may be wondering who created EternalBlue in the first place? The origins of the SMB vulnerability are what spy stories are made of — dangerous NSA hacking tools leaked, a notorious group called Shadow Brokers on the hunt for common vulnerabilities and exposures, and a massively popular operating system used by individuals, governments, and corporations worldwide.

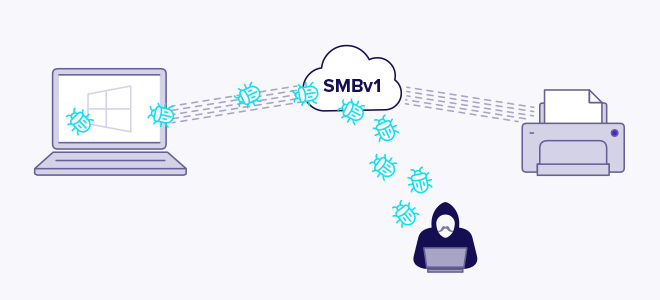

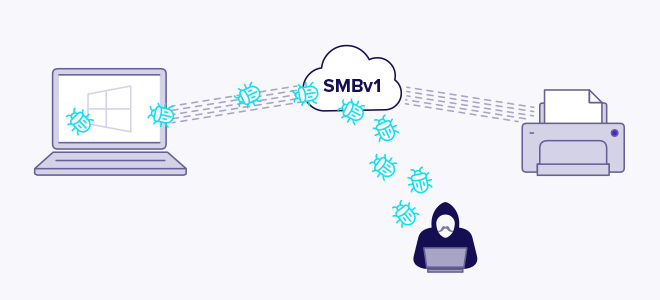

How does EternalBlue work?

The EternalBlue exploit works by taking advantage of SMBv1 vulnerabilities present in older versions of Microsoft operating systems. SMBv1 was first developed in early 1983 as a network communication protocol to enable shared access to files, printers, and ports. It was essentially a way for Windows machines to talk to one another and other devices for remote services.

The exploit makes use of the way Microsoft Windows handles, or rather mishandles, specially crafted packets from malicious attackers. All the attacker needs to do is send a maliciously-crafted packet to the target server, and, boom, the malware propagates and a cyberattack ensues.

EternalBlue's Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures number is logged in the National Vulnerability Database as CVE-2017-0144.

Microsoft’s patch closes the security vulnerability completely, thus preventing attempts at deploying ransomware, malware, cryptojacking, or any other worm-like attempts at digital infiltration using the EternalBlue exploit. But a key problem remains — for many versions of Windows, the software update must be installed in order to provide protection.

It is this key problem that gives EternalBlue such a long shelf life — many people and even businesses fail to update their software regularly, leaving their operating systems unpatched and thus vulnerable to EternalBlue and other attacks. To this day, the number of unpatched vulnerable Windows systems remains in the millions.

EternalBlue is both the given name to a series of Microsoft software vulnerabilities and the exploit created by the NSA as a cyberattack tool. Although the EternalBlue exploit — officially named MS17-010 by Microsoft — affects only Windows operating systems, anything that uses the SMBv1 (Server Message Block version 1) file-sharing protocol is technically at risk of being targeted for ransomware and other cyberattacks.

How was EternalBlue developed?

You may be wondering who created EternalBlue in the first place? The origins of the SMB vulnerability are what spy stories are made of — dangerous NSA hacking tools leaked, a notorious group called Shadow Brokers on the hunt for common vulnerabilities and exposures, and a massively popular operating system used by individuals, governments, and corporations worldwide.

How does EternalBlue work?

The EternalBlue exploit works by taking advantage of SMBv1 vulnerabilities present in older versions of Microsoft operating systems. SMBv1 was first developed in early 1983 as a network communication protocol to enable shared access to files, printers, and ports. It was essentially a way for Windows machines to talk to one another and other devices for remote services.

The exploit makes use of the way Microsoft Windows handles, or rather mishandles, specially crafted packets from malicious attackers. All the attacker needs to do is send a maliciously-crafted packet to the target server, and, boom, the malware propagates and a cyberattack ensues.

EternalBlue's Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures number is logged in the National Vulnerability Database as CVE-2017-0144.

Microsoft’s patch closes the security vulnerability completely, thus preventing attempts at deploying ransomware, malware, cryptojacking, or any other worm-like attempts at digital infiltration using the EternalBlue exploit. But a key problem remains — for many versions of Windows, the software update must be installed in order to provide protection.

It is this key problem that gives EternalBlue such a long shelf life — many people and even businesses fail to update their software regularly, leaving their operating systems unpatched and thus vulnerable to EternalBlue and other attacks. To this day, the number of unpatched vulnerable Windows systems remains in the millions.